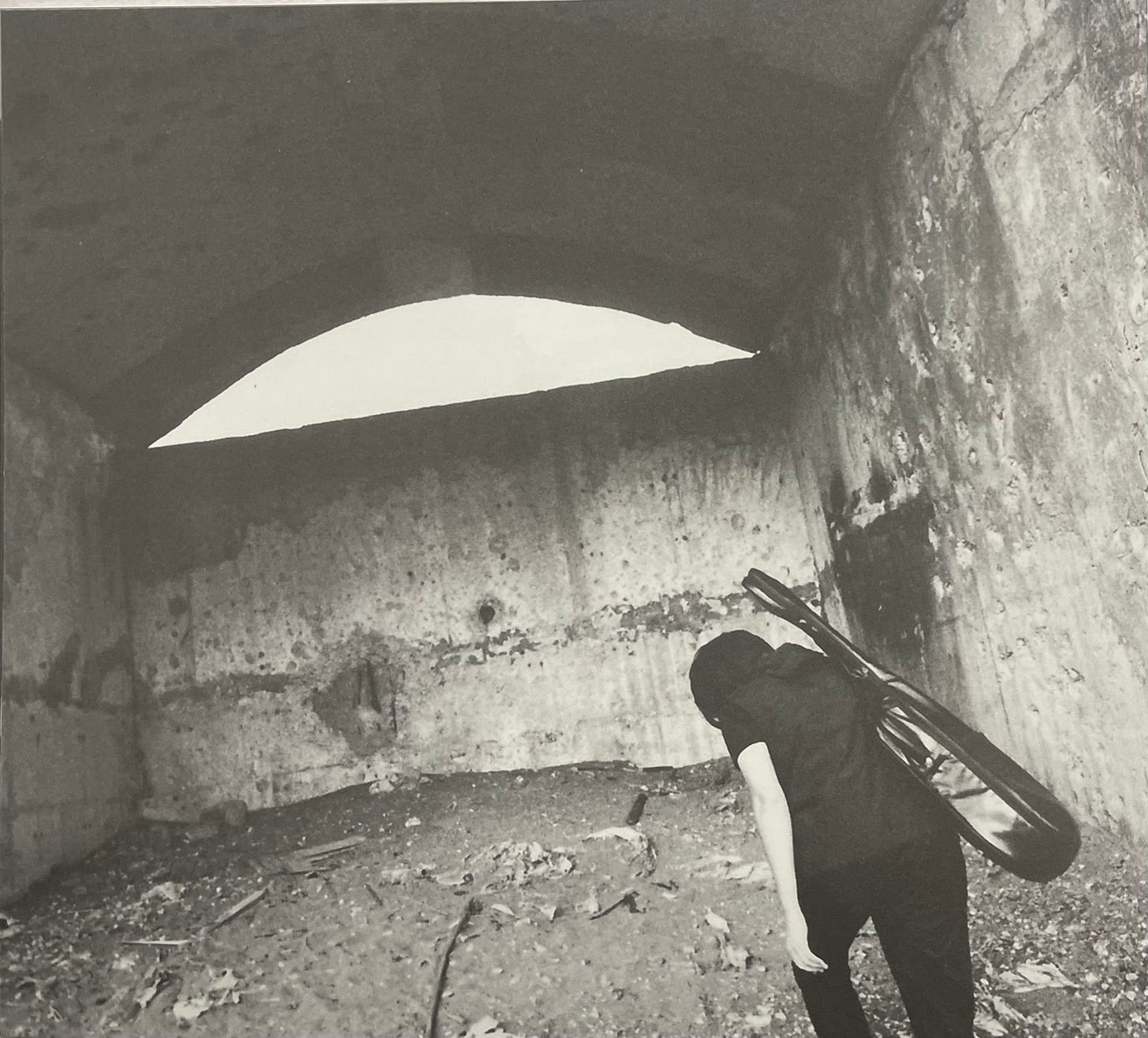

巴奈 Panai's "泥娃娃 Ni-wa-wa"

An epic of environmental storytelling from one of Taiwan's finest folk singer-songwriters

My second favorite way of finding new artists, after attending live shows at random, is through album collaborations. The artist I’m talking about this week, Panai (巴奈), is one that I first heard this way, through a feature on the song “Swan” off the debut album of one of my favorite Taiwanese rock bands, Elephant Gym. This was several years before I arrived in Taiwan, and at that time, Panai’s full albums were not easily located online, so while I had listened to some of her songs, I didn’t become a real fan until more recently1.

Shortly after getting to Taiwan, I made the decision to get into collecting vinyl, with a focus on artists whose albums it would be harder to get back in the states. At one of the first record stores I went to, I stumbled upon Panai’s album 泥娃娃 Ni-wa-wa2 and, recognizing the cover art from the songs I had looked up on youtube years ago, it became the first Taiwanese record that I bought. It took buying the physical vinyl to get me to revisit Panai’s music, and to be blown away by her incredible voice and exceptional songwriting talent.

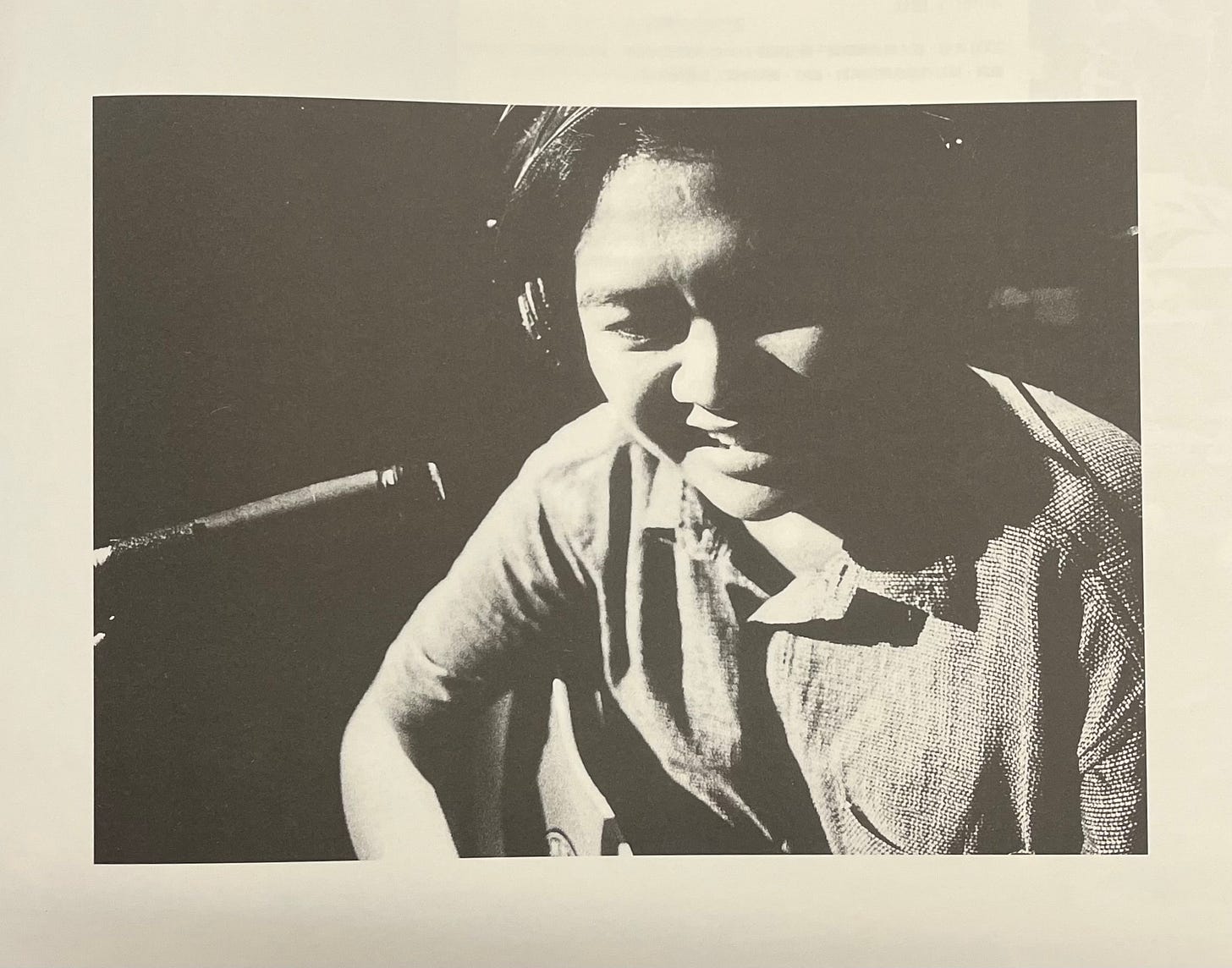

I feel slightly embarassed about having gotten into Panai’s music in this roundabout way, given that she is a pretty significant name in the modern landscape of Taiwanese folk music. Born to parents of the Puyuma and Amis indigenous tribes of Taiwan, Panai Kusui is not only a musician, but a social activist leader and strong advocate for indigenous land rights in Taiwan. She has also been called the “Tracy Chapman of Taiwan” by some, and while I am not the biggest fan of artist comparisons like that3, I recognize the cultural impact that it implies. All said and done though, I’m glad to have gotten hooked on her music, regardless of how I got there.

Ni-wa-wa 泥娃娃 is Panai’s first album, recorded and released in 2000 while she was working as a singer in a western restaurant in Yilan. Despite being her debut, the album has a developed style and clear vision. Inspired in part by Panai’s experience with being a wanderer, leaving her home in Taitung at a young age and moving through Kaohsiung, Taichung, Lukang, Taipei, and other places in search of work, the album distills the impressions of places both familiar and unfamiliar. Moving through these sonic environments, Panai’s powerful voice and distinctive melodic style bring the human aspect of wandering to the fore, expressing what it means for a person to be integrated or isolated, and how it feels to be lost, or listless, or longing for home.

A lot of environmental storytelling in Ni-wa-wa is done through sound design. The track “pauai流浪記/Wandering” starts off with a rough, old-sounding recording of a folk song accompanied by stilted, out of tune strumming on a string instrument and the sound of ocean waves. This leads into the bulk of the song, which is a enka-flavored ballad with electric organ support. The main part of the ballad is positioned as a response to the recording at the beginning, whose simple adage of:

我的爸爸媽媽叫我去流浪

My parents told me to go wandering

我一面走一面掉眼淚

I shed tears as I walked

is complicated to recieve; it rings partly true for Panai, even when it feels too simple. Between verses of singing “我實在不想輕易讓眼淚流下/I don’t want to let tears fall easily,” we get interludes of aboriginal singing, calling back to the “home at the foot of the mountain” that Panai is leaving, signalling that as much as Panai would like it to be an easy goodbye, it won’t be. Four minutes of ballad are punctuated by a two minute instrumental outro as the aboriginal songs and classic instrumentation give way to bitcrushed drums, slap bass, trippy drones, and Panai’s own voice, now far away, singing with effects and reverb. The fear of growing away from the place and person once known is captured perfectly in the breakdown, until subtly, at the end, it all fades into the same ocean sounds from the beginning.

Not all the tracks have such an involved arc to them, though. Many are content to build and sit in a single environment and emotion. “浮沈/Floating, Sinking” creates the unsettling ambience of a broken and desolate merry-go-round with this creepy static pipe organ and slightly canned waltz playing on the piano. The spooky backing band rolls on and on, accompanying a depressed vocal melody which sings itself in circles. Audio fuzz, unintelegible reversed tape recordings, and distorted electronic wails in the backround establish a cold mechanical feeling, and overly heavy rubato makes the entire band feel like a broken wind-up toy, with the ends of certain phrases grinding nearly to a halt before the vocal refrain picks them back up. While the song doesn’t go anywhere, that’s the point; it captures the bleakness of wandering, the feeling that the sadness is somehow inescapable.

The album makes use of these more static environmental songs to tell stories in another way, also. By juxtaposing the vibes captured in two different tracks, Panai can narrate a journey stepwise, highlighting the places and moments that brought her out of a rut and into a realization. After exploring the low point of loneliness in “浮沈/Floating, Sinking” and “捆綁/Tied Up in Knots,” Panai sings “大武山美麗的媽媽/My Beautiful Mother, Da-Wu Mountain,” a jublilant rendition of indigenous Taiwanese singer Kimbo Hu’s folk song that celebrates their shared hometown of Taitung. At the start, the song is quiet and intimate, and you can even hear some wavering in Panai’s voice. Soon, though, we hear cheers and chatter coming from other surrounding voices, and Panai’s tone softens — suddenly sounding like she’s singing through a smile. Before long, the other people join in, first as background ooohs and aaahs, then one by one joining in on the verse and chorus. Each of these voices has its own individuality (there’s this one man with this amazing gravelly voice which just exhudes joy and warmth), and as they grow louder, more raucous, and more jubliant, Panai lets loose, strumming on the guitar without abandon and belting out with the chorus:

有一天我一定要回去為了山谷裡的大合唱

One day I must go back for the chorus in the valley

我一定會大聲唱歌再也不走了

I will surely sing loudly, and never leave again

In the context of the low spirits Panai has been in after wandering aimlessly, this song gives one possible answer to the spiral of misery and self-doubt: community.

Panai creates stories through song interactions even among non-consecutive songs. The song “天堂/Heaven” from the back half of the album reappropriates the same two chords from the opening track “泥娃娃/Ni-wa-wa,” but this time, plays them through a fuzzy and distorted baritone electric guitar (rather than the pure-toned acoustic on the first track). Sort of like a stopped record, the guitar repeats one chord at a time, only moving on when Panai moves on, and there is a wavering white noise in the background evoking a gray and messy landscape. The lyrics express Panai’s helplessness with herself, unable to be who she thought she could be, or do what she thought she could do. Appropriating a torn-apart version of the childrens song sung at the beginning to express these feelings of depression and failure shows the arc of experience since the start of the album, calling back to mind the childlike innocence that Panai has since lost.

With how important the background sound environment is to Panai’s storytelling, you’d expect it to be present across every track. But, on “失去你/Gone is Gone4” Panai entirely forgoes any complex sonic palette in favor of bare-bones voice and guitar, with no effects or environmental noise to speak of. Once again, though, this is a choice in service of storytelling. “失去你/Gone is Gone“ is a heartbreaking, lullaby-like tune about the plain fact of loss, and the futility of trying to explain away or rationalize the sadness surrounding it. ”失去你就是失去你 (Losing you is just losing you),” Panai sings. “無所謂會不會再想你 (It doesn’t matter if I will miss you again).” The stripped down production on the track allows Panai to use a more wavering, vulnerable vocal performance to really sell this feeling — the only times her voice breaks on the album are on this song.

Panai’s dynamic vocal performances are, in fact, another storytelling tool in her arsenal. In particular, the way that she messes with timing and uses rubato is incredibly effective and well thought out. I’ve mentioned a few examples above, like the stopping and starting in “浮沈/Floating, Sinking,” but my favorite example on the album is in the song “捆綁/Tied Up in Knots.” The song is about feeling trapped, tied up in a negative worldview of your own making. The verse, which expresses this listless feeling, is delivered over a repetitive 6/8 feel with a plodding regularity. In contrast, in the chorus, the band opens up into a 2-beat feel, and Panai bursts free in an impassioned outcry with an absolutely wild amount of rubato. Completely untethered from the beat, Panai criticises herself:

看這世界是沈重的心 喔能不能不再懷疑

Seeing this world is a heavy heart Oh, can you stop doubting it?

聽聽自己沈重的心 也可能只是少了勇氣

Listen to your heavy heart Maybe you just lack courage

The extremely free delivery with which Panai sings the chorus is not only beautiful, it’s incredibly apt for the structure of the song. To break free of the cycle of inaction, restlessness, and fear, Panai literally breaks free of the song’s tempo and rhythm, finally sparking a change in herself.

This idea, that questioning yourself and the world around you is what allows you to break out of the cycle of isolation and fear is, in my mind, one of the central messages of the record. The narrative climax of the album, “你知道你自己是誰嗎/Do You Know Who You Are?” expresses hope in a path to change, but minces no words in its call to action. It barrages the listener with question after question, asking:

你知道你自己是誰嗎?

Do you know who you are?

你勇敢的面對自己了嗎?

Are you brave enough to face yourself?

The questioning doesn’t stop at the self, either. Panai also asks us if “this world is like what we imagined (這個世界是你所想像的嗎?).” In both of these endeavors, she challenges us to think for ourselves, uncompromisingly.

是真的已經無路可走了嗎?

Is there really no way out?

你無法讓自己的心平靜嗎?

Can’t you make your mind calm down?

你無法讓自己更有勇氣嗎?

Can’t you let yourself have more courage?

The album doesn’t leave us only with questions, though. The warm, folksy final track, “每一天/Every Day’s Dream,” talks about going through life in a lonely world, one with so many people, but where no one is ever that closely connected. Having told us the story of her struggle with this reality across the earlier tracks of the album, Panai ends by offering her simple, hard-won advice:

看人單純一點 誤解再少一點

Look at people more simply, and misunderstand people less

會不會更自由一點 更安心一點

Wouldn’t that be more free, and less worrying?

Happy Listening!

Also at the time, I was in high school. Was this a factor in being not as receptive to folk music? Who can say.

The english title is Ni-wa-wa, a transaliteration rather than a translation. The term refers to a type of clay doll, and is also the title of the well known Chinese children’s song which Panai interpolates in the album’s title track.

Principally because it seems to set up a sort of power imbalance in which the only bar for greatness is one that compares against a western counterpart; but also just because they’re both their own artists who bring their own things to the table.

As is often the case, the official english song titles aren’t always direct translations. 失去你 means simply “losing you.”